The Scoop

A candidate running to be New York state’s chief money manager says he would pull the state’s huge pension fund — the third largest in America — away from Wall Street firms.

Drew Warshaw is running for New York state comptroller, a job most voters would struggle to define but one that includes oversight of the state’s pension fund. If he unseats 18-year incumbent Thomas DiNapoli, Warshaw’s plan is to move much of its nearly $300 billion of investments into ultra-cheap, passive index funds.

The New York State and Local Retirement System has more than $90 billion invested in private equity, private credit, real estate, and other complex assets. All promise high returns — catnip for pension managers facing future payouts to retirees — but charge high fees, too.

The question facing New York and hundreds of other state and local pension funds, charitable endowments, universities, and government funds around the world: Are these high-priced managers worth the fees they’re charging?

Historically, yes. Since the 1970s, these “alternative” investments — so named because they aren’t publicly traded stocks or bonds — have provided an edge. But that’s been less true recently, as big tech stocks like Microsoft and Nvidia have soared. And now that alternative managers are chasing mom-and-pop investors, there are real questions about whether they can keep beating the broader market.

Warshaw doubts it’s worth trying, though he says he’ll dig into each fund. NYSLRS has fallen short of its assumed rate of return — the investing profits it believes it needs to meet its obligations to pensioners — in six of the past 15 years, according to data from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research.

“My starting position is ‘deeply skeptical’ and that these alternative asset classes have to prove their value,” Warshaw said in an interview. “With all this capital flowing into private markets, at some point you’re going to regress to the mean” and be left with subpar returns, after fees.

That was Brad Lander’s assumption when he became New York City’s comptroller in 2021, overseeing the city’s pension fund.

“I came in as a private-equity skeptic,” Lander said. He replaced the fund’s chief investor, who had a long history in private markets, with one from index giant State Street, and ordered a review. Instead, he ended up seeking permission from the state legislature to increase the fund’s exposure to private markets, which now accounts for 25% of its investments. “My team convinced me that, even with higher fees, we would be better off,” he said. “But it requires discipline. It’s a healthy debate to have.”

Know More

Warshaw knows he’s running for a job most voters don’t understand, and has borrowed from Zohran Mamdani’s playbook, posting videos on social media of him dropping fistfuls of cash and giant novelty checks off on Fridays by Wall Street’s bronze bull statue.

His opponent in next year’s Democratic primary is DiNapoli, New York’s longest-serving statewide elected official.

Warshaw said an analysis produced by researchers at Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research found that, had NYSLRS met its handpicked benchmarks, the fund would be about $100 billion larger today. Semafor confirmed the performance data and benchmarks that Stanford used, which are available from NYSLRS’s public reports, but not the underlying analysis of returns.

The New York state pension has lagged its benchmark over one, three, five, and 10-year timeframes in private equity and private credit. It has beaten its benchmarks over all four time periods in public stocks and bonds, where it largely uses passive strategies. It has paid about $9 billion in fees to outside managers over that decade, public filings show.

About two-thirds of New York pension fund’s $113 billion in public stocks are currently in index funds, according to its latest annual report. The rest is managed by about 40 outside firms, whom Warshaw said he’d replace with passive strategies that mirror stock and bond portfolios at a fraction of the cost. He said he would “take a closer look” at its $50 billion in private equity, managed by firms including Blackstone, KKR, and Vista Equity; its $12 billion in private credit; and $35 billion in real estate and infrastructure.

“It has been trying and failing to beat the market,” Warshaw said. “I don’t think taxpayers should be funding something that’s impossible.”

“Anyone can cherry-pick comparisons,” a spokesman for DiNapoli said. “We have full confidence in the strength of New York State’s pension fund. The returns from our asset allocation continue to provide retirement security for our more than 1.2 million working and retired members and their beneficiaries.”

Step Back

Warshaw, 44, never worked on Wall Street, which helps explain his antipathy toward the idea that it has a secret sauce. He was chief of staff at the Port Authority as it rebuilt Ground Zero, then went to Columbia Business School — where the “Day One lesson was ‘don’t try to beat the market’ and the most popular class was some version of ‘how to beat the market,’” he says, a disconnect that informs his current campaign. He quit a housing nonprofit in May to run against DiNapoli, who was appointed by the state legislature in 2007 and reelected four times without facing a Democratic primary challenger.

Plenty of pensions and endowments have missed out on gains over the past five years because they spread their money around across the world and different investment types. That means they own less of the big tech stocks that have soared and been more exposed to bumps in real estate, international stocks, and interest rates.

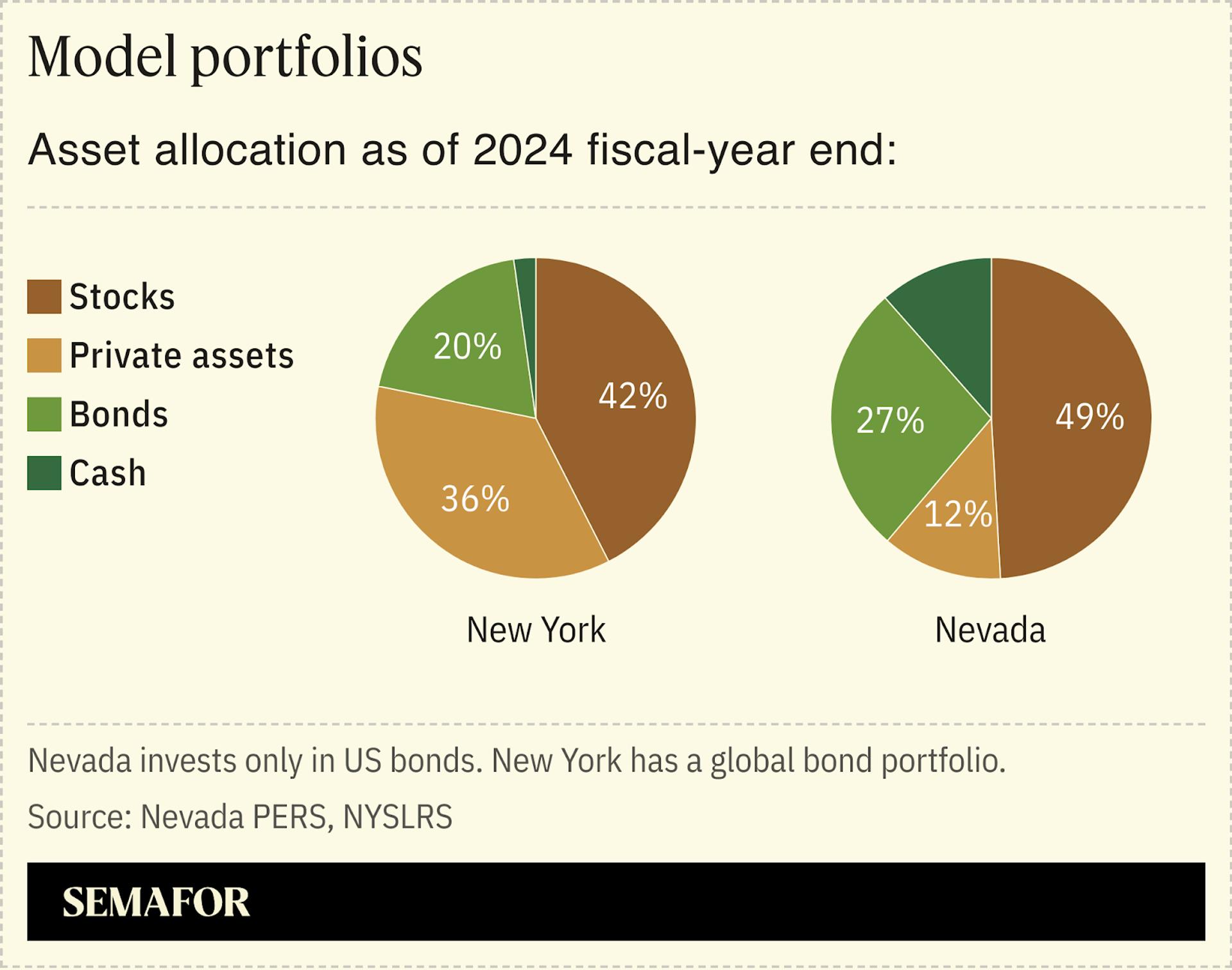

As a model to emulate, Warshaw points to Nevada, which by the early 2010s put most of its pension money into passive index funds. It invests a small amount in riskier bets through third parties that serve as no-fuss feeders to private equity and venture capital firms. “New York is not Nevada,” DiNapoli’s spokesman said.

“The KISS — ‘keep it simple, stupid’ — model has paid off very well over the past few years,” said Chris Aillman, who stepped down in June as chief investment officer of the California State Teachers Retirement System, the second-largest public pension in the US. “If only it were so simple to pick those seven stocks in hindsight.”

Unusually, New York state lets a single official decide how to invest its pension money. It appears that only Connecticut has the same setup, after North Carolina’s governor signed a bill in June to shift investment oversight to a board.

Liz’s view

Searching for alpha is a noble cause, and investors always want to think they can find profits others have missed. Private investors had an edge for a while, playing on the margins of unloved corporate entities and capitalizing on post-2008 regulations that hamstrung bank lending. But the more money they raise, the more they will whittle away at their advantage. President Donald Trump’s executive order this week allowing private assets in 401(k) accounts could bring trillions more into the space, which will inevitably hurt returns. This happened long ago in leveraged buyouts — the wildcatters at KKR returned 40% or more from their early funds and now the industry calls half that a home run —and it will eventually happen in other areas of investing.

Passive will come to alternatives, too, right around the time we stop calling them alternatives. Today there is no S&P 500 index for private equity, but BlackRock — whose index funds put plenty of active mutual-fund managers out of business by showing their flaws — is quietly working on a fix. Apollo and State Street just launched an index fund for private credit and more are coming.

The View From Brad Lander

ESG investing may not be as fashionable as it was a few years ago but public pensions, whose beneficiaries are union members in largely Democratic-leaning cities and states like New York, remain committed. Lander says he’s far more effective pushing those ideas through New York City’s pension plan’s private investments than its public ones, where efforts to needle Amazon and Starbucks on unionization fell flat.

Lander pressured Apollo — in whose private funds it’s a major investor — into protecting union jobs at the Venetian hotel in Las Vegas, and bought the mortgages of 35,000 rent-stabilized housing units from the failed Signature Bank last year. “If we hadn’t done that, I think it’s quite likely a bottom feeder could have bought those,” he said.

“The core responsibility is obviously delivering strong returns,” Lander said, “but you just have a much more direct impact” by investing directly in private markets.

Notable

- “Still boring after all these years,” Pensions & Investments magazine wrote in 2020 of Idaho’s retirement system, which loosely follows the Nevada model.

- Long after ESG investing has lost its shine, two professors in June advocated a more expansive view of public pensions as “embodiments of public values, not vehicles to maximize beneficiary wealth.”